Indigenous languages around the world are in critical danger of extinction, particularly Native American languages in the United States. Each year, there is heartbreaking news of a fluent speaker passing away in Indian country in which the cultural knowledge and language dies with them. Yet despite this language loss epidemic, there doesn’t seem to be any priority for the U.S. government to help tribal nations save their languages; the same government that stole these languages away from Native people during early times of colonization. While many Indigenous languages have laid to rest or are just a few years from extinction, language warriors from tribal communities around the country have dedicated their lives to reviving their languages back to survival status. There is a belief around Indian country that without knowing your language, you can’t possibly know your cultural identity; it is the foundation of the culture and who you are as a Native American person. Ceremonies, prayers, and many oral traditions are all communicated in the native tongue, which is at the heart and center of many tribes.

Our language at one time was spoken by 100% of our people. The current state of our communities’ health is directly linked to the state of deterioration that our language is in.

– Típiziwin Tolman, Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

Of the 574 recognized Tribal Nations in the United States, each have their own unique language and identity, but only about 155 of those languages exist in some form today. Language revitalization programs, like the Lakȟól’iyapi Wahóȟpi (Lakota Language Nest) on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation or the ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ (Cherokee Language) Master Apprentice Program in Cherokee Nation are just two examples of many that have had success in bringing back their languages to speakers today. There are many challenges associated with language revitalization because most were only orally spoken and never a written language. Bringing together linguistic experts, translators and educators with fluent speaking Native elders has been an interesting challenge in documenting these languages into written form. Molding Indigenous languages to fit into the modern approach of teaching them in schools is something Native American tribes have never had face before and goes against the ways these languages have always been historically taught.

IMAGE CAPTIONS:

Evereta and her Mustang: photographed in Tse’Bii’Ndzisgaii (Monument Valley) with her Ford Mustang. She is a Diné (Navajo) woman working in the education system with hopes of one day opening up a cultural and language immersion school for her people.

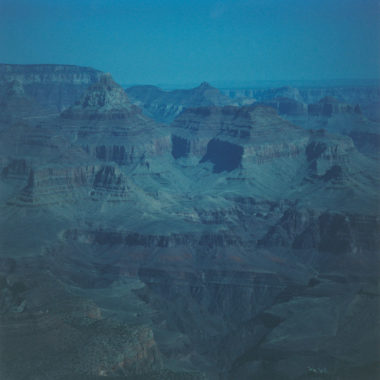

Amanda and Linda: Amanda (left) and Linda (right) Teller come from a family line of singers. Amanda’s grandmother started the Diné singing group called the “Chinle Valley Singers”, made up of all women that travel the world performing their songs. “My grandma composed most of the songs when she was herding sheep,” says Amanda, “and by continuing to sing and perform my grandma’s songs is our way we keep the traditions, language and culture alive in my family.” The mother and daughter are photographed at Canyon De Chelly within Navajo Nation.

Maka in his classroom: Maka teaches Lakota studies at Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. After traveling the world and teaching English in Japan, he realized his calling was going back to the Indian Reservation to teach his own people & inspire kids to explore life off the reservation.